Chapter 13 USS Growler [SSG 577]

Growler began her sea trials on 4 November 1958 in the traditional submarine test area off the Isle of Shoals. A successful first day was spent on the surface conducting full power runs, testing various ship systems and cycling all masts. At dawn on 5 November 1958, the Growler crew prepared to conduct the first test depth dive. After submerging to periscope depth, she then proceeded deeper, leveling off at 50 foot increments as the crew checked all systems and hull fittings subject to sea pressure. As Growler passed the fleet-type submarine test depth of 475 feet, the majority of her crew were in new territory, never having been this deep before. Everything was fine until Growler reached 75 feet short of her test depth.

Radioman Leonard Powers was in the Radio Shack directly across the passage way from the Sonar Room. Powers remembers hearing a loud pop and looking across the passage way towards the source of the sound only to find a stream of water roaring down from an empty one-half inch cable fitting in the overhead of the Sonar Room. Captain Priest immediately ordered "Emergency Surface" while everyone nearby grabbed buckets and began collecting the water, passing it along to the galley for disposal. Most of the water was flowing into bilges or staying within the four- inch deck coaming that surrounded the Sonar Room. Unlike most of the crew's experience on the fleet-type submarines, where the compressed air rushed into the ballast tanks during an emergency surface evolution, at this much greater depth the air seemed to barely hiss. Lieutenant(jg) Robert Duke, the Communications Officer, was monitoring the depth gauge in the Chief Petty Officer's quarters and recalls the strange sensation of Growler slowly rising to the surface with a slight down angle due to the flooding. Growler surfaced with only superficial damage., The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Planning Superintendent, Lieutenant Commander Hank Hoffman, went topside and determined that an unused cable fitting opening had been plugged with a temporary blank for dockside tests which had not been replaced prior to sea trials. With all the time lost and additional costs if they returned to port, Hoffman suggested to Captain Priest, Jr. that a solution was readily available on board. The cable hole was slightly smaller than the diameter of a nickel and with two nickels sandwiching a rubber gasket, Hoffman was able to securely plug the hole. A compartment air pressure test indicated no leakage present and the trials resumed with torpedo firing and other ship's system tests. The temporary plug was removed in the shipyard, mounted on a plaque with the label "The Cheapest Repair in Shipyard History," and was the start of the ship's commemorative plaque collection.,

On 15 November 1958 Growler conducted her first missile operation test when she launched a 56 foot long, 13 ton dummy mass sled balanced to simulate a Regulus II missile. Much to the chagrin of shipyard officials, the first three attempts failed due to electrical problems. On the fourth try, the sled was successfully launched, splashing into the ocean 2,000 yards away as planned.

1959

With acceptance trials completed, Growler headed south for her shakedown cruise. After successful completion of torpedo firing trials, Growler headed for Naval Air Station Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico and the start of her Regulus I launch operations. Growler's first missile launch took place 24 March 1959. Since the BPQ-2 Trounce guidance equipment was not yet installed, USS Runner (SS 476), a Regulus guidance submarine, took control immediately after launch and guided the missile during the 30 minute flight. The next flight was a two-boat Trounce guidance operation in combination with USS Argonaut (SS 473) and Runner and was again successful.

Growler completed another three launches, all successful, over the next two weeks. Missile operations were then brought to an abrupt halt by a failure in the launcher elevation mechanism. The Short Rail Mark 7 (SR MK 7) launcher was overly complicated due to automatic sequencing and safety controls. Elevation was controlled by limit switches that were positioned to prevent the elevation screws from over extension. These switches failed and the launch rails were forced off the screws, stripping the top of the threads in the process. Repair was seemingly impossible since the boat did not have the necessary tools to re-cut the stripped threads. Captain Priest remembers that, without being asked, off-duty crew members would come topside to take turns trying to repair the threads by filing them back into shape with hand files. He realized his efforts to bring to the crew the team spirit so necessary to successful operation of a submarine had been successful.

Growler returned to Portsmouth for post-shakedown availability. The launcher was modified to prevent the recurrence of the limit switch failure. The BPQ-2 Trounce guidance radar and electronic equipment installation was also completed. During this time period Growler received orders to her new home port, Pearl Harbor. One guidance submarine, USS Medregal (SS 480) and the other East Coast Regulus I launch boat, USS Barbero (SSG 317), were also moving to Pearl Harbor as all Regulus I operations were being consolidated in the Pacific. Growler departed Norfolk 27 July 1959. After several days in Key West, Florida, where she put on several missile ram-out demonstrations, Growler left 14 August 1959 for transit to Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal.

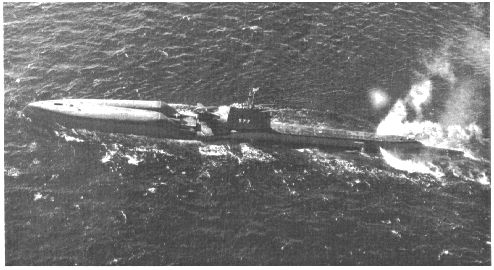

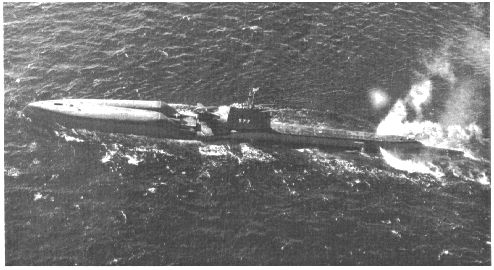

During the long and slow transit the crew and had one memorable swim call. On 26 August 1959, Captain Priest and the Executive Officer, Lieutenant Commander John C. "Pete" Burkhardt decided it would be appropriate to make a movie, from the surface, of Growler at periscope depth, snorkeling and then surfacing, ramming out a missile and running the missile engine up to full power. A life raft was inflated and a volunteer crew consisting of Lieutenant(jg) Robert Duke, Lieutenant(jg) William Lindeman, Torpedoman First Class John Haney and Commissary Steward Oscar Weigant, paddled 50 yards off to start filming. While submerged and circling the raft, Priest recalls observing the raft and seeing everyone waving quite energetically. He took this to mean that the filming was working out well. When they surfaced and recovered the raft, Priest learned the rest of the story. Duke recalls:

"It was very, very quiet and actually pretty lonely in the raft, even with three fellow volunteers. After successfully filming Growler as she submerged, we were preoccupied with trying to ward off shark attacks. While we were watching for the periscope, I felt a heavy rippling along the bottom of the raft. After the second time, I asked Lindeman, Haney and Weigant if they felt it. They had and as we talked I looked over the side of the raft and saw a six-foot shark pass under the raft, turning to try to take a bite out of the raft's underside. I calmly asked for the shark repellent and received a

There is no shark repellent, Sir.' I then asked for the flare gun and received a

There is no flare gun, Sir.' We were completely ill-equipped and were about to face the consequences. I took an oar, ready to hit the shark the next time it made a pass. Meanwhile, Weigant was standing up, waving a shirt at the periscope he had just spotted. I felt sure we were all about to be dumped into the water. After I got Weigant to sit down; and, with Haney paddling like mad towards the periscope, the shark made another pass and this time I managed to give it a good rap on the nose. Much to my amazement, the shark disappeared for the next five minutes.

Meanwhile, Growler surfaced 100 yards off the raft and prepared to ram out the missile. The movie camera was on the floor of the raft, bouncing around in the salt water, useless. The shark returned but this time he had a friend which was quite a bit larger. The newcomer never made a run on the raft but the smaller one continued to worry us.

As Growler approached to recover us, the sharks, of course, disappeared and everyone on board remained skeptical of our story."

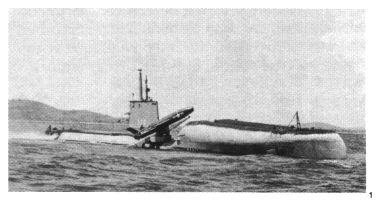

Growler arrived at Pearl Harbor 7 September 1959 and was assigned to Submarine Squadron ONE. Missile operations resumed on 2 October 1959 with the first Trounce guidance flight for the Growler guidance team. The operation was successful and the missile recovered at Bonham Auxiliary Landing Field on the Island of Kauai. Growler's first tactical missile operations took place in late October with two highly successful and accurate terminal dives to impact. Her first unsuccessful launch occurred 8 December 1959 when the missile did not program over to cruise settings and splashed astern. Over the next three months she launched an additional three missiles, including two tactical missiles for warhead development testing. Prior to her first deterrent strike patrol, in nine launch operations Growler had lost one missile at launch and none while in flight (Photo #12).

Regulus Deterrent Patrols 1960-1964

Growler's first deterrent patrol began on 12 March 1960. A major

problem during transit to her assigned patrol station was the gradual

loss of both aluminum sheet metal fairings around the missile hangar

doors. Started by corrosion due to electrolysis between the aluminum

and steel and exacerbated by the heavy seas encountered in the miserable

North Pacific winter weather, the aluminum fairings disintegrated and

were lost overboard. During this first mission, Lieutenant John J.

"Joe" Ekelund, Executive Officer and Navigator, developed an innovative

method to determine the submarine's position in the assigned operating

area. The technique was quite simple and similar to that used by

submarines to determine the range of a target ship. Using navigation

charts, Ekelund identified mountain peaks and their height as listed.

He then observed the mountain through the periscope and, utilizing the

built-in periscope stadimeter, he could superimpose the image of the

base of the mountain on its peak. This double image and known peak

height provided a good approximate range to the mountain that was read

on the stadimeter dial. Using the range so determined, one can could

calculate the amount of height which was not seen (was below the

horizon) and correct the charted height to the observed height. Using

the observable height a second, more accurate range could then be

measured. Three iterations of this sequence would yield a

navigationally useful range. Using more than one peak, he could

accurately determine his position.

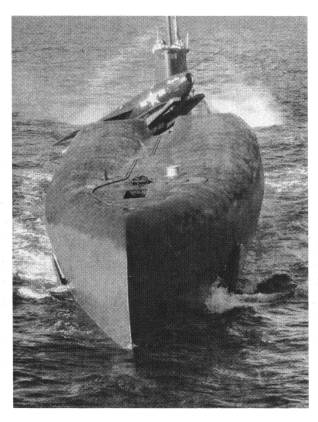

Growler's first deterrent patrol began on 12 March 1960. A major

problem during transit to her assigned patrol station was the gradual

loss of both aluminum sheet metal fairings around the missile hangar

doors. Started by corrosion due to electrolysis between the aluminum

and steel and exacerbated by the heavy seas encountered in the miserable

North Pacific winter weather, the aluminum fairings disintegrated and

were lost overboard. During this first mission, Lieutenant John J.

"Joe" Ekelund, Executive Officer and Navigator, developed an innovative

method to determine the submarine's position in the assigned operating

area. The technique was quite simple and similar to that used by

submarines to determine the range of a target ship. Using navigation

charts, Ekelund identified mountain peaks and their height as listed.

He then observed the mountain through the periscope and, utilizing the

built-in periscope stadimeter, he could superimpose the image of the

base of the mountain on its peak. This double image and known peak

height provided a good approximate range to the mountain that was read

on the stadimeter dial. Using the range so determined, one can could

calculate the amount of height which was not seen (was below the

horizon) and correct the charted height to the observed height. Using

the observable height a second, more accurate range could then be

measured. Three iterations of this sequence would yield a

navigationally useful range. Using more than one peak, he could

accurately determine his position.

Ekelund remembers that the first "interesting" experience on this patrol involved the Number One periscope. Growler was snorkeling at night and the Conning Officer reported to Ekelund that he had sighted a white object. With no sonar contacts reported and no ice seen during the previous several hours, a complete sweep of the horizon revealed white objects completely surrounding the boat. They had sailed into an ice field. Immediately all masts were lowered but not before the periscope was hit by a large ice flow, damaging it enough to render useless. Priest and Ekelund both recall that from then on the mission was routine, except when it came time to head back to Pearl Harbor. On 2 May 1960 the mission was extended three days after Gary Powers' U-2 aircraft was shot down over the Soviet Union. Morale sagged temporarily when this announcement was made. After seven weeks on station in terrible weather, even three days was a major burden. Growler returned to Pearl Harbor on 12 May 1960.

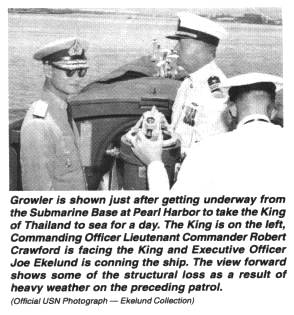

Priest was relieved by Lieutenant Commander Robert Crawford on 7 June 1960. Crawford had served on Regulus guidance submarines on the West Coast and was returning to submarine duty after completing a tour in the Bureau of Aeronautics at the submarine-launched guided missile desk. The day Crawford reported for duty was the same day a catastrophic fire occurred on USS Sargo (SSN 583). Ekelund recalls that at about 1700 hours he heard a fire alarm sounding on the base. He went to the bridge and saw columns of smoke over the buildings in the direction of nearby piers. Sargo was on fire, with the flames being fueled by a break in the oxygen transfer line in the stern compartment. The fire was finally extinguished by flooding the stern compartment.

Growler and her crew became involved when Crawford was asked to be host of the King of Thailand during his State Visit since Sargo was now no longer available. A good part of the rest of the night was taken in making all of the myriad of preparations, including meals during the cruise, planning for proper honors, alerting all of the crew that the uniform would be Full Dress Whites with swords. The day went perfectly and the crew and officers of Growler were justifiably proud that when COMSUBPAC needed something done well without prior planning, they had been selected.

One month later Growler was awarded the Battle Efficiency "E" for overall excellence in Submarine Squadron ONE during the previous year. Launch operations resumed in August with two fleet training missile flights and then a tactical missile low-level profile flight. This flight was somewhat different in that the Growler missile team launched the missile on shore at Bonham and transferred control to the Growler guidance team on board the submarine for the remainder of the flight. The missile was expended as planned.

Growler's second deterrent mission began 10 November 1960 and she

returned to Pearl Harbor 18 January 1961. After two months upkeep and

two successful missile launches, she left 18 March 1961 on her third

mission. Lieutenant Commander Robert Owens had reported to Growler as

Prospective Executive Officer in February and was serving as Assistant

Ordinance Officer. He recalls that the transit to Adak, Alaska for

refueling and then to the assigned station was uneventful. One morning

he went up to the bridge to shoot the morning star sight. Unfortunately,

dense fog lay on the water surface and there was no discernible horizon.

The bridge was above the fog layer while the deck, perhaps 20 feet below,

was completely hidden. Suddenly the electronic countermeasures alarm

began to blare from the speaker on the bridge. The operator realized it

as being transmitted from a Soviet ship. Due to the intensity of the

transmission it was determined that the ship was close aboard. Crawford

and Owens simultaneously observed a radar mast suddenly appear above the

low lying fog. Apparently Growler was inside of possible radar

detection range. Crawford made the decision not to dive in order to

avoid possible sonar detection. Growler changed course to head directly

away from the contact and escaped undetected.

Growler's second deterrent mission began 10 November 1960 and she

returned to Pearl Harbor 18 January 1961. After two months upkeep and

two successful missile launches, she left 18 March 1961 on her third

mission. Lieutenant Commander Robert Owens had reported to Growler as

Prospective Executive Officer in February and was serving as Assistant

Ordinance Officer. He recalls that the transit to Adak, Alaska for

refueling and then to the assigned station was uneventful. One morning

he went up to the bridge to shoot the morning star sight. Unfortunately,

dense fog lay on the water surface and there was no discernible horizon.

The bridge was above the fog layer while the deck, perhaps 20 feet below,

was completely hidden. Suddenly the electronic countermeasures alarm

began to blare from the speaker on the bridge. The operator realized it

as being transmitted from a Soviet ship. Due to the intensity of the

transmission it was determined that the ship was close aboard. Crawford

and Owens simultaneously observed a radar mast suddenly appear above the

low lying fog. Apparently Growler was inside of possible radar

detection range. Crawford made the decision not to dive in order to

avoid possible sonar detection. Growler changed course to head directly

away from the contact and escaped undetected.

Growler returned to Pearl Harbor 12 May 1961. Lieutenant Commander Donald Henderson relieved Crawford 24 June 1961. During the change of command ceremonies Growler was awarded a Submarine Force Unit Citation by Rear Admiral Roy S. Benson, ComSubPac, for her previous mission. Growler immediately entered Pearl Harbor Navy Shipyard for overhaul. One addition was the installation of a Sperry Gyroscope Mark I Mod 0 Ships Inertial Navigation System (SINS) and the first LORAN C navigation system. A second modification during overhaul was an attempt to improve the handling characteristics of Growler at periscope and snorkeling depth. The problem was one of fluid hydrodynamics. The top of the missile hangar fairings were nearly one-half the height of the sail. At periscope depth this made for some difficult handling and a roller coaster ride as the Bernoulli effect caused the hangar deck area to act like an airplane wing and make the boat move towards the surface. This was especially apparent in rough weather. While Grayback and Growler had nearly identical exteriors, Grayback had a slightly different shape to her missile hangars that lessened this unwanted Bernoulli effect. By adding 10 feet to the height of Growler's sail, the hangar surfaces would be 10 feet deeper at periscope depth and in theory, depth keeping problems would be somewhat mitigated. This also meant adding 10 feet to each of the periscopes, communications and radar masts as well as the electronic countermeasures equipment and snorkel. This was not a small undertaking by any means. The additional height of the sail changed considerably the metacentric height, a measure of ship's stability. To prevent excessive rolling on the surface, additional saddle ballast tanks was added outboard of the main ballast tanks.

A welcome modification was also made to the missile launching equipment. The original trainable and transversable launcher that had been designed to launch both Regulus I and II missiles was removed and replaced with one that simply transversed to either missile hangar for missile ram out. Launch was forward over the missile hangars. The removal of the myriad of microswitches and associated hydraulics greatly simplified launcher operation and made this launcher much more reliable. Growler completed her overhaul in early December 1961.

1962

After eight weeks of refresher training, Growler left Pearl Harbor on her fourth deterrent patrol on 11 February 1962, arriving at Midway Island five days later to disembark a sick crewman. Leaving Midway Island the next day, Growler arrived at the patrol area on 24 February 1962. Growler departed for the forward refit base one month later, arriving. 24 April. After a four week repair and upkeep period, Growler departed 24 May 1962. Arriving on station in early June 1962, she commenced her fifth deterrent patrol. Growler returned to Adak on 23 July 1962, departing for Pearl Harbor the next day. Lieutenant Commander Gunn, now Executive Officer, had a battle flag that read "Black and Blue Crew, No Relief Required!" They were flying this banner upon return to Pearl Harbor on 1 August 1962. Rear Admiral Bernard A. Clarey, ComSubPac, joined Growler as she entered Pearl Harbor and upon seeing the unfurled flag flying on the mast, put his hand on Henderson's shoulder and asked if they really meant it. Henderson responded that it was true, the Regulus submarine crews took great pride in the fact that they did not need the Blue and Gold two-crew system used in the Polaris submarines. Growler received a ComSubPac Unit Commendation for both the fourth and fifth patrols.

After a 30 day upkeep, Growler began her customary refresher training with both torpedo and missile firing exercises. Submarine officers who aspire to command of a submarine must undergo a series of rigorous qualifying tests, exams and practical evaluations, all under the watchful eyes of the senior officers on board. Henderson remembers a most memorable prospective commanding officer evaluation that took place at this time. One of the steps in the evaluation process requires that the candidate personally prepare an exercise torpedo for firing. This meant supervising the loading of the torpedo on board, acting as the Approach Officer (assuming the position of the Commanding Officer during the attack) and upon gaining a satisfactory firing solution, fire the torpedo.

The operating area was off of Barbers Point, Oahu. By seagoing standards, the area was reasonably close inshore but not dangerously so. Areas such as this were frequently utilized to reduce the transit time for torpedo recovery vessels. The assigned target was a Pearl Harbor- based submarine rescue vessel. Lieutenant Gene Wells, the ship's Torpedo Officer, was being evaluated and had done very well up this particular day. His fire control party attained a firing solution on the target's speed course and range. Well's fired his personally prepared torpedo and just like in the movies, he started a stopwatch to time the period of the torpedo run to determine when it should intercept the target and in this case, locate the torpedo after the run. Exercise torpedoes were set to run in one of two modes, either high speed short range or low speed and long range. Usually one would select the high speed option to minimize the opportunities for targets sighting the torpedo and maneuvering to avoid being hit.

Wells selected the high speed option, but, due to equipment malfunction, it was not entered into the torpedo. For reasons that were never clear, the torpedo ran the low speed, long range run. Henderson recalls everyone counting down the time with no result, i.e., the torpedo could still be heard whining away. It kept running and running and running and then the sound finally stopped. Both Wells and Henderson were at the periscopes and were astonished at what they saw. To their amazement, as the whining sound stopped, they saw the torpedo break the water surface and run up the beach, finally coming to rest between two large fuel storage tanks in the Barbers Point fuel farm!

One can only imagine the initial response of the torpedo retrieval team back at the base when Growler requested a cherry-picker retrieval crane to proceed to the middle of the naval air station fuel farm. Wells passed his torpedo firing test since on the balance, the shore-based fuel facility was considered a worthwhile target.

Growler's sixth deterrent patrol, the third with Henderson in command,

began on 24 November 1962. Weather in the assigned station area was

again miserable. For Christmas dinner Henderson decided to go deep so

the crew could enjoy the meal in relatively stable conditions. A

thousand foot floating wire antenna permitted Growler to submerge to

three hundred feet and still receive messages. While wave motion could

still be felt at 300 feet, the meal was really much more enjoyable. A

novel relief during this patrol was contributed by a Quartermaster

Second Class who had been on board Growler for all six patrols.

Traditionally, daily routine reports are made to the Commanding Officer

at 0800, 1200, 1600 and 2000 hours. The 1200 hours report consisted of

fuel and water on board, magazine and missile hangar temperatures,

average specific gravity of both the forward and aft battery cells,

ship's position and that all chronometers (precision time pieces set to

Greenwich Mean Time) had been wound and compared with each other. This

report was normally made to the Commanding Officer during lunch. The

other officers present paid little attention since it was usually so

monotonous and routine. On this particular day this Quartermaster

Second Class gained everyone's full attention when he recited the

following poem in place of the routine report:

Growler's sixth deterrent patrol, the third with Henderson in command,

began on 24 November 1962. Weather in the assigned station area was

again miserable. For Christmas dinner Henderson decided to go deep so

the crew could enjoy the meal in relatively stable conditions. A

thousand foot floating wire antenna permitted Growler to submerge to

three hundred feet and still receive messages. While wave motion could

still be felt at 300 feet, the meal was really much more enjoyable. A

novel relief during this patrol was contributed by a Quartermaster

Second Class who had been on board Growler for all six patrols.

Traditionally, daily routine reports are made to the Commanding Officer

at 0800, 1200, 1600 and 2000 hours. The 1200 hours report consisted of

fuel and water on board, magazine and missile hangar temperatures,

average specific gravity of both the forward and aft battery cells,

ship's position and that all chronometers (precision time pieces set to

Greenwich Mean Time) had been wound and compared with each other. This

report was normally made to the Commanding Officer during lunch. The

other officers present paid little attention since it was usually so

monotonous and routine. On this particular day this Quartermaster

Second Class gained everyone's full attention when he recited the

following poem in place of the routine report:

Good afternoon Captain and the rest of you

Here's the good word from the O.D. and the crew.

The chronometers wound just about nine

Then checked and compared with Greenwich Mean Time.

1 ... 2 ... 5 ... 2 is the gravity now

And since we've submerged its bound to go down.

The magazines checked and found to be well.

With temperature normal, 51 sounds swell.

Now I don't wear a mask and I don't hide my face.

The noon reports lately have been a disgrace.

So I'll make this poetic to keep up the pace.

Now thanks for your patience in hearing me out

I'll see you tomorrow, on that there's no doubt.

Needless to say, this got everyone's attention and a lavish round of applause. Growler returned to Pearl Harbor on 11 February 1963 and received a COMSUBPAC Unit Commendation for this patrol. In addition, CINPACFLT issued a Unit Citation to all officers and men of Submarine Division ELEVEN for the period 1 November 1961 to 27 June 1963.

Lieutenant Commander Robert Owens relieved Henderson on 1 June 1963. Growler conducted two more deterrent missions, 14 June 63 to 12 August 63 and 14 October 63 to 13 December 63. In early 1964 the decision was made to decommission Growler and Grayback. Growler and Grayback sailed for Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California together and were decommissioned in May 1964.

Post Regulus, the Growler Museum

After decommissioning on 25 May 1964, Growler was placed in the Inactive Reserve Fleet at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Washington. Twenty- five years later it was decided that she was a burden to the annual budget and the Navy decided to use her as a torpedo test target for nuclear attack submarines. Fortunately these tests were never conducted. Instead, through the efforts of Mr. Zachary Fisher, of New York, and by an act of Congress, on 8 August 1988, Growler was assigned to become part of the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum in New York City. In early 1989, Growler departed Puget Sound under tow. Proceeding through the Straits of San Juan de Fuca, she began a journey of six thousand nautical miles. After transiting the Canal, Growler was towed to a civilian shipyard on the west coast of Florida. While in the shipyard, Growler received both exterior and interior hull repairs, most important of which were the changes made between the missile hangars and the hull. These changes were made to facilitate access for visitors at the museum. On 18 April 1989, Growler was moored to the north side of Pier 86 in the Hudson River, her final "Home Port." The entire cost of this operation was absorbed by Mr. Fisher, founder and chairman of the Intrepid Sea- Air-Space Museum. On 26 May 1989 Growler was "re-christened" at Pier 86 and is now one of the most popular exhibits of the Intrepid Museum complex.

Appendix V: Aspects of Regulus Submarine Construction and Operation

While Tunny and Barbero were conversions of "fleet type" submarines, Grayback, Growler, and Halibut were new construction. Several specific aspects of their construction are described here.

Engine Installation on Grayback and Growler

New design diesel-electric engines were installed in Grayback and Growler. Recent diesel-electric submarines such Albacore, Tang, Trigger, Trout and Wahoo had received General Motors "Pancake" engines where the cylinders were vertically stacked above the generator. These engines had a very high horsepower-to-weight ratio, ran at high speed and took up much less space then the World War II diesel engines. Harder, Darter, Gudgeon, Grayback and Growler got the Fairbanks Morse aluminum block, high speed engines which also took less space and had a higher rated horsepower to weight ratio then the General Motors engines.

In the case of Grayback and Growler these engines were also shock and sound isolated, previously done only in the three "K" class hunter- killer submarines of the early 1950's. Since these engines were operating at about twice the speed of other diesels, they generated noise at a higher frequency. Since higher frequencies are attenuated underwater much faster then low frequencies, in theory, the sound detection range was much shorter.

The major drawbacks in both of the new engine installations were discovered only after operational testing. Both engine types were unsatisfactory, with broken crankshafts, cracked liners, piston failure, fatigue failures of injectors and injector fuel tubing, burned out exhaust expansion joints and much more. The joke amongst the crew and the designers was that both General Motors and Fairbanks Morse had been about 100 pounds too successful in their weight reduction program. Very small increases in strength and rigidity would have made the engines highly successful.

Growler Patrols:

12 Mar 60 - 17 Mar 60

10 Nov 60 - 18 Jan 61

18 Mar 61 - 24 May 61

11 Feb 62 - 24 Apr 62

24 May 62 - 01 Aug 63

24 Nov 62 - 11 Feb 63

14 Jun 63 - 12 Aug 63

04 Oct 63 - 13 Dec 63

REGULUS: THE FORGOTTEN WEAPON TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ......................................................... iii Preface ........................................................... v Acknowledgments .................................................. vii PART I: A NEW ERA IN WEAPONS SYSTEMS Chapter 1: Guided Missiles - A New Weapon System ................. 1 PART II: REGULUS I AND II FLIGHT TEST AND DEVELOPMENT Chapter 2: Chance Vought Enters the Missile Business ............. 19 Chapter 3: Regulus I Flight Test and Development 1950-1952 ....... 30 Chapter 4: Regulus I Flight Test and Development 1953-1956........ 66 Chapter 5: Regulus I Flight Test and Development 1957-1966 ....... 92 Chapter 6: Regulus II Flight Test and Development 1952-1958 ..... 103 Chapter 7: Regulus II After Cancellation ........................ 128 PART III: REGULUS I DEPLOYMENT ABOARD AIRCRAFT CARRIERS AND CRUISERS Chapter 8: Regulus I and Carrier Aviation ....................... 137 Chapter 9: Regulus I and Heavy Cruisers ......................... 161 REGULUS I DEPLOYMENT ABOARD SUBMARINES Chapter 10: USS Tunny (SSG 282) ............................... 174 Chapter 11: USS Barbero (SSG 317) ............................... 209 Chapter 12: USS Grayback (SSG 574) ............................... 234 Chapter 13: USS Growler (SSG 577) ............................... 250 Chapter 16: USS Halibut (SSGN 587) .............................. 263 PART IV: APPENDICES AND GLOSSARY Appendix I: Guidance Systems for Regulus I and II ............. 275 Appendix II: Guided Missile Support Unit Histories ............. 301 Appendix III: Guidance Submarines ............................... 318 Appendix IV: Nuclear Warheads for Regulus I and II ............. 319 Appendix V: Regulus Submarine Characteristics, Construction ... 324 Appendix VI: Regulus Submarine Deployment Schedule ............. 328 Appendix VII: Regulus Flight Operations and Production Summary .. 329 Appendix VIII: List of Interviews ................................ 335 Glossary.......................................................... 338

![]() Return to the USS Growler Museum

Return to the USS Growler Museum

Copyright © 1996 "Regulus: The Forgotten Weapon"

by David K. Stumpf, Ph.D.

Turner Publishing

All rights reserved.